Electronic Journal of Academic and Special Librarianship

v.8 no.3 (Winter 2007)

Electronic Journal of Academic and Special Librarianshipv.8 no.3 (Winter 2007) |

|

Doug Suarez, Reference Librarian and Subject Specialist for Sociology and Applied Health Sciences

Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada

dsuarez@brocku.ca

How do we know what students are really doing in the library when they are studying? This paper reports on a study that used qualitative methods to assess what students were doing during the winter term at Brock University. The goals were to try and establish if they were engaged in their studies when using the library and to see if the library nurtured academic engagement in its study areas.

Academic libraries have always had a mandate to provide effective and efficient library services to all members of their constituency -- students, faculty, and staff. With the evolution of academic libraries into information commons, learning commons or similar configurations where libraries share and offer related academic support services with other units on campus, there is an even greater urgency to evaluate service mandates.

As the major component of an academic leave during the winter term at Brock University, I intended to explore the possibility of developing an evaluative tool for assessing library effectiveness and efficiency that could be useful to library administrators and planners, as well as library staff, in performing their daily library professional practice. The research question I had was: Are students engaged when using the library, particularly when using study spaces? I wanted to find out what behaviors students were exhibiting in an academic library when students were using study areas, and if these behaviors appeared to be learning engaged. Did students appear to be engaged while using study areas, or did they use the library as a convenient place to spend time doing other things when they were not in class? As a corollary to this I was also interested if library study areas provided suitable means for engagement when students used them.

The usual method of measuring service quality has been to focus on service delivery and customer satisfaction within the framework of a marketing model, and traditionally using questionnaires and surveys to quantify data. A good example of this approach that specifically assessed the impact of reference services at an academic library found that friendliness of reference staff was one of the best predictors of students’ confidence in their ability to find useful information on their own (Jacoby & O’Brien, 2005).

Before gathering data with methods like questionnaires, intensive interviews, and counts of the behaviors that are being assessed, I thought it would be more prudent to do preliminary diagnostic explorations. Good survey results depend on data that is collected using viable and reliable measuring instruments, and these in turn depend on developing concepts based on empirical research. In this instance we need to know something about study behaviors, as observed and expressed by students, before we can realistically quantify the extent of these behaviors and if these support academic engagement.

The behaviors I was interested in are those exhibited by students that take place in the library study areas. Some of these support the main purpose of the library (and more specifically the library study areas) and could be classed as engaging, while other behaviors may not be engaging, in and themselves, but supportive nevertheless. Lastly, other behaviors may be otherwise and at odds with the library’s main purpose.

Library staff at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, recently completed a learning commons study (2007). This is a good example of a study that used both qualitative and quantitative methods to assess student usage of library facilities for planning purposes. However, very little research has been done on study space use from a user’s perspective. Bennett (2005) makes the point that we need to ask the right questions by refocusing on the modes of student learning rather than on library operations when librarians attend to planning exercises. The quality of learning, how students learn, and how libraries can capitalize on this knowledge is more important than measuring frequency and ease of use of standard library services.

According to Bennett two important questions to ask in planning for library design include: time on task and what educationally purposeful activities students do when outside of class. O’Connor (2005) studied student intellectual life from an anthropology perspective at Sewanee University. A large part of this research included the library as a primary place where students spent a significant portion of their time on campus when they were not in class. Students studied a lot in the library and O’Connor found that a well-designed library supported scholarly activities and social context where students felt comfortable, secure and cared about. Other researchers have found that most students of the millennial generation expect academic libraries to be comfortable, have refreshments in the library, and provide library resources from off campus as well as having wireless networking on campus (Duck & Koeske, 2005). Learning environments and their influence on students’ engagement and learning have been studied by educators who have been interested in the interrelationships between study behavior, approaches to study, and student learning and the acknowledgement that there are multiple variables that influence these environments (Entwistle & Peterson, 2004).

The approach in my study was a specific application of a broader research orientation that studies man-environment relations in general. The sociologist John Zeisel’s work was instrumental in providing the initial framework for my study. Zeisel (1975) quotes the psychologist Roger Barker in defining the concept:

A behavior setting is both a physical environment and its behavioral characteristics. Describing behavior settings includes a least an understanding of what people generally do there, how people know what is expected of them there, how norms of behavior are established, which attributes of the physical environment tell potential users what is expected of them, and what the environment is like. A behavior setting is not merely a physical concept, nor is it purely social. It links the two together into what can be seen as a primary social-physical unit. (p. 11)

My research study looked at study behavior as an example of educationally purposeful activities. It was an exploration and evaluation of behaviors that take place in library study spaces. The research design was a case study of the study areas located on the main floor and stack floors of the James A. Gibson Library. The library had various areas designated as group and individual study areas and included individual study carrels, group study areas with tables, movable chairs and soft seating. The main floor was the primary study focus but other floors were also included but to a lesser degree. The research was intended to be holistic, conducted in a natural, real-life library situation, and the subjects of the study were students who used study areas in the library.

This study was qualitative and used ethnographic methods. The design was flexible and emergent. It evolved as understanding of learning behaviors increased. The sample was small and emphasized depth rather than breadth. I was not overly concerned, in this study, with sampling a wide range of Brock students to gauge their use of study areas. I was interested in what those students who used library study areas did while in the library. The students who were observed in the study areas were part of an ever-changing group of students who used the library study facilities. Some were familiar faces to me in my role as a reference librarian, while others were faceless and part of the crowd. Those students chosen for interviews were purposefully chosen as being study-space users and not randomly chosen from the general student population.

The two primary techniques used in the study to gather data were participant observation and semi-structured interviews. Environmental behavior observation of student activities in study areas and individual student interviews were employed with some additional informal interviews of selected library staff to get staff perspectives of what they observed students doing in study areas while they were doing their jobs in the library.

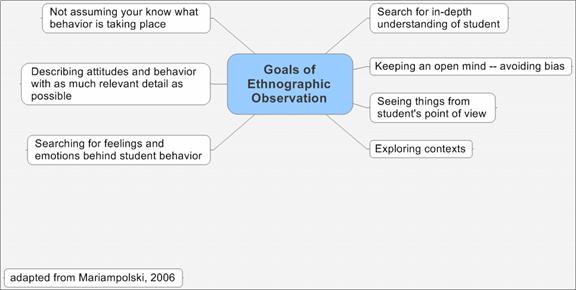

The data was intended to be gathered over a six-month period of observation in the field, and data analysis was based on discovering patterns of behavior that emerged from detailed description and interpretations of the data that gave meaning to the behaviors taking place. The analysis and conclusions reached in this study were grounded in the actual data gathered and presented in a narrative style that is normally characteristic of qualitative studies. Figure 1 summarizes the goals of ethnographic observation.

This study utilized both impressionistic and systematic observation as the primary data gathering techniques. Observing student behaviors in study areas allowed me to see unintended behavior that students took for granted and could not always report or reproduce in subsequent interviews. Observations also were very useful for capturing activities that were not always reported by participants in interviews.

Many commonplace activities may seem trivial, unimportant, or not worth mentioning even though they may be important to the researcher. Other activities may not be reported in interviews because they may appear to be embarrassing or against the rules or accepted norms of behavior in certain contexts. An example of the former case would be the sequence of events that constitute “using the computer”, and an example of the latter would be burping or yawning while chatting with a colleague. The assumption is that some of these behaviors that are taken for granted by either the person performing the actions or the observer may be important in certain contexts, in this case the library and its mission mandate to support academic learning.

Figure 1. Goals of ethnographic observation

A significant part of my research included participating in situ. I not only spent time observing student behavior in study areas, but I also worked in these study areas as a researcher. I sat at study carrels or study tables everyday, at different times of day, with my notes, journal, and readings and spent time doing research. In appearance, I dressed casually, and I assumed I was largely indistinguishable from other students, apart from perhaps being seen by other students as a more mature student. I cared my backpack, outer clothes, lunch and other paraphernalia with me, parked them down at my study area and went about the business of doing my work in the same manner as any other student would with theirs.

The activities of my work day included: coming and going; reading; taking notes from my readings; writing observations in my journal; doing literature searches on the library computers; searching for materials in the stacks; and related activities. I ate snacked or ate lunch at my desk in my usual casual grazing style, brought in mugs of tea and sipped water all day long.

During the day I occasionally talked with some students, in a casual manner, for various work related reasons or otherwise, or with library staff and colleagues if I crossed their paths. I did not make a habit of fraternizing with colleagues and it did not take very long for them to simply ignore me most of the time. My laboratory was the library study areas and I was an integral part of the environment. In short, I was in the field.

I found that individual student interviews were useful for me. I wanted to understand the student point of view on their use of the library and establish rapport with student participants. Student interviews needed research ethics board approval from Brock University. This was obtained in March and interviews proceeded with individual students in March and April. The sample size was small, 8 students. I had allowed for a sample size of 8 to12 and purposefully chose students who I had seen use the library study areas. I wanted to interview students who use the study areas, not potential users, so this meant choosing students I saw using study areas. I wanted students who seemed to use the study areas frequently, and I wanted students who were interested in participating. Some of the participants were familiar faces to me, as students. I had sometimes assisted some of them in the past at the reference desk or had met some of them in similar library service contexts. Others were not known to me but agreed to participate when I approached them. Some students did not participate in spite of agreeing to initially. I suspect that time constraints affected their decisions at the time (end of term and exams).

The interviews were semi-structured and used open-ended questions with various probe questions inserted as necessary in order to keep the interview conversation going. What students thought the library meant to them, the library’s role in supporting student endeavors, how they used study spaces, were examples of the questions I asked to try and get their perceptions of, and meanings attached to, specific library places and services.

The sessions were micro-recorded, lasted from 30 – 60 minutes, and took place in a private setting (Data Research Service Office) on the main floor of the library. Appendix 1 outlines my interview questions.

I selected a few library employees that I thought might be able to provide me with valuable insights into student behavior because of the nature of their jobs. For example, stacks staff regularly saw students on all floors during normal working hours when they are collecting and shelving library materials. These interviews were informal, did not include a set of questions and took place during break times or similar circumstances.

Interviews helped confirm my own observations, refine my observations and methods and helped me interpret the observational data. Results were be used to triangulate data to reinforce its reliability and viability.

In condensed form my general observations, behavior clusters, and the types of behaviors are summarized below. Appendix 2 details my observations and interview notes more fully.

General observations:

Behavior clusters:

The behaviors I observed and/or self-reported by students in interviews included:

Types of behavior

From these clusters, I attempted to classify them in various ways. In analyzing my journal entries and interview transcriptions I found some themes that immediately became self-evident although some of them were overlapping. Often it was an interpretation on my part that attempted to group them in ways that made sense to me. Some individual behaviors could easily be interpreted in different ways depending on the context at the time of inquiry.

Identifying engaging behaviors, or those behaviors that support student learning were sometimes the most difficult to differentiate. In fact, these groupings are not mutually exclusive and may depend on the observer’s perspective bias and the contexts these behaviors are being observed in. My categories are engaging, social, and leisure behaviors.

Hu & Kuh (2002) refer to engagement as essentially the quality of effort that students devote to educationally purposeful activities. These activities are generally ones that contribute directly to desired academic outcomes. Milem & Berger (1997) and others further acknowledge that both activities in the social domain as well as the academic domain are important for enhancing student engagement.

Examples of engaging behaviors were:

All of these could be observed whether students used notes, books, journals, computers, cell phones or communicated face-to-face with other students.

Some behaviors are more obviously of a social nature than others. Examples are:

Some behaviors are mostly leisure in nature:

Throughout my study I was cognizant of the difficulty of trying to determine which behaviors could be distinguished from others that would provide evidence of academic engagement. Do we really know what students were doing in these study areas, or was the truth really more relative? It may simply be all a matter of perspective. Katzer, Cook and Crouch (1998) point out that people learn to see and they interpret what they see depending on context. Figure 2 below summarizes the author’s error model.

Figure 2. Error Model

During the planning stages of my case study, well before I began to actually do my observations of student behavior in the study areas of the library, I wondered where I would do most of my observations. In which study areas would I spend the most time doing observations? My initial inclination was that I would probably spend most of my time on the seventh floor of the library. This was where the library provided a combination of quiet group study and individual study carrels. I thought I would feel most comfortable there and I would be able to blend in well and not be distracted by excessive noise.

The other main areas that I thought I would spend time in were on the main floor where the large group study area was located and where there was a combination of quiet study carrels and private group study rooms. I initially did not think I would spend much time in these locales because I perceived them as being very noisy and generally, to my way of thinking, not conducive to my idea of studying. I also thought that students were mostly goofing around, socializing, and not really working (studying) very much in the group study areas. In fact, many of my colleagues referred to this area as the pit, not a term that suggested serious, academic behavior.

My perspective was biased. It contained assumptions and value judgments that influenced my perception of the situation and guided my initial behavior. However, once I began my observational studies, I quickly realized that I did have a bias and that there was a wealth of good data to be obtained by observing these areas on the main floor. I continued to observe in different parts of the library but gravitated to the main floor once I overcame my bias, or perspective.

Charon (1998) suggests that the best definition of perspective is a conceptual framework “which emphasizes that perspectives are really interrelated sets of words used to order physical reality. The words we use cause us to make assumptions and value judgments about what we are seeing (and not seeing)” (p.20). These perspectives are neither true nor false even though we may be tempted to put value judgments on them. They are helpful, or otherwise, if they are acknowledged and dealt with. Observations and their interpretations help us make sense of the situation and can change over time or depend on context.

The relationship between perspective, perception of a situation, and the action is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Meaning of Perspective

At the end of the day, the questions I have to acknowledge when I observed library study areas are: what have I really seen; are students demonstrating behaviors that we could say are academically engaging? What one observer interpreted as study behavior (e.g., a student writing an essay or what appears to be an assignment) might just as well be a behavior that includes writing but the student could have been writing a grocery list or a personal letter.

Furthermore, I am also aware that observations might be biased in the other direction. The halo effect, or the tendency to see most aspects of a person’s behavior in a positive light, could also be a factor in my study. The small sample and the way the sample was selected could have biased me toward seeing what I wanted to see; that is, behaviors that were engaging, and vice versa.

This project was a qualitative case study on the use of library study space. It was an empirical investigation of student study behaviors in an academic library during the winter and spring terms of the academic year, 2006-2007. It employed participant observation, unobtrusive observation, and interviewing to collect evidence of study behaviors. The task was to discover what behaviors were exhibited by students when they used library study areas, to differentiate these behaviors if possible, and to discover whether or not these behaviors supported academic engagement. These behaviors were expected to emerge as the study progressed.

It was a naturalistic, descriptive and exploratory research that sought to identify study behavior themes. The behaviors identified suggested that students were generally pursuing behaviors that were engaging and supporting the academic mission of the library. Like similar academic libraries, the James A. Gibson Library, is a socio-cultural institution that exists to support the academic mission of the university by:

O’Connor’s study at Sewanee University identifies three cultures that exist on campus that students socialize into during their total time spent at university – collegiate, academic and campus (O’Connor & Bennett, 2005). Of these three, academic culture is the one that the library naturally represents. Academic libraries have traditionally been home to academic pursuits. Knowledge is acquired in the form of collections and new knowledge creation is supported by providing access to these collections and by providing access to other collections through library services. Unlike the classroom, the activities that academic libraries support and promote are reading, writing, and study in the general sense. Classrooms are where academics teach. Collegiate culture is generational and transitional between high school and workplace, marriage, and other adult commitments. Campus culture is institutional and reflects specific practices that bind both academic and collegiate cultures together.

Bennett (2005) argues that libraries need to evolve from service organizations (providing services to patrons as if they were mere consumers) to organizations that primarily promote and support learning.

Using participant observation, and mainly observing students working in the library in designated study areas on the main floor and seventh floor, as well as secondarily observing students using study carrels on other library floors, my initial impression is that students are pursuing study behaviors (engaged in activities that one would normally expect to find in an academic library), and these behaviors are mostly academic activities that support their course work here at school. They are attentive and involved in what they are doing. The library is providing an atmosphere that encourages these behaviors.

In spite of some initial thoughts about the high level of noise, high pedestrian traffic, social gatherings and general “hubbub” in the group study area on the main floor, my observations show that students are working on course work most of the time. Even when it may appear that small groups of students are “chatting”, or eating/drinking, flirting, or whatever, they are also generally studying as well.

Behaviors that students exhibit in the library appear to be practical activities and goal-oriented behaviors. These behaviors can be grouped together as behaviors that involve a range of skills, routines, and habits that are probably learned over time and appear consistent with a wide range of behaviors that support academic engagement. These behaviors can be called study behaviors and examples of these include reading, writing, consulting with fellow students, using computers to do literature searching, communicating with others, and writing assignments.

Some of the behaviors observed can be grouped together as leisure or social behaviors but these, on the whole, do not seem to distract from academic work being done in the library. Students using cell phone, personal sound devices, or chatting, or napping are generally not the main behavioral activities observed although they do appear. The context of academic learning takes precedence and these other activities seem to promote personal relaxation, and social bonding between students. I noted that similar patterns were reported by students in my interviews for other areas on campus that students often studied in. These included classrooms during times when the classrooms were not in use (e.g., weekends), and computer labs (e.g., faculty of business, computer commons, other labs).

In addition, it was clear to me that students acknowledged that there were distractions that they wanted to avoid, at times, when studying. They wanted as much physical comfort as possible to help them study. They wanted convenience. They wanted quiet areas to get away from others so they could concentrate better. The nature of their assignments was a powerful factor in their preferences for group study areas.

Finally, the pattern I have described here is fluid not static in nature. Depending on a range of factors, student preferences and predilections, students adapt to their surroundings.

Libraries can be viewed as information ecological systems or examples of information ecology (Nardi & O’Day, 1999). Human activities are served by technology supports, and library employees, library practices, library values, and student behaviors largely conform to the system. Most activities that take place in the library are academic in nature, both by definition and execution. The system evolves naturally, over time, as values change and activities change with them. In this sense, the James A. Gibson Library is a prime example of such a system.

The library can also be viewed as part of a learning community. Students create their own learning spaces by using facilities provided by the library and enhancing them if possible to accommodate their study activities. The forthcoming evolution of the library into a learning commons and the library’s own vision statement will try and create structures more conducive to the development of a learning community.

The community that students participate in while at university can be viewed as an integral part of a socialization process where it is assumed that students learn in groups throughout their lives. At Sewanee University, O’Connor (2005) summarizes his research study with high praises for his university library and how it fits well with the college’s overall mission:

Any well educated person appreciates the unity, worth and community of knowledge. That’s what a good library offers and students need to learn before they leave. After all, wedded to practicality, the workplace does not and cannot readily teach these vital values. (p.73)

The learning community a Brock is an example of a purposeful integration of the various social worlds and cultures that students participate in and learn from. This is an assimilation process.

If researchers are interested in obtaining numerical data to test hypotheses that assess student study behaviors in the context of academic libraries, then further work needs to be done to quantify engaging behavior. From these observed behaviors, concepts need to be defined and tested, survey questions need to be developed and tested for validity and reliability, and then subsequently used in proper survey instruments. The techniques used in this study could be useful in providing input for library usage studies, including studies using quantitative survey methods. Before being able to develop meaningful questions for questionnaires and surveys, the results from an environmental study such as this could be used as building blocks to contribute to developing hypotheses to test in subsequent studies. Figure 4 summarizes aspects of student engagement.

Figure 4. Student engagement

What can we do to foster engaged behaviors in the library? Even if we cannot define and measure precisely, we can recognize context and behaviors we think are congruent with academic goals of the library.

A research project correlating student success with study habits as observed in this study could be an interesting study of the effectiveness of some studying styles over others. A related project that focuses on certain groups of students (e.g. more senior students in a particular faculty), their study habits (e.g. whether or not they prefer to use quiet or group study areas in the library) and their grades (e.g. self-reported) could be done. The results would be useful for planning future study areas.

Figure 5 provides a summary of working principles that enhance student engagement in the library and learning commons environment.

Figure 5. Enhancing student engagement

Thank you for meeting with me today. This interview is being audio recorded and all information will remain confidential. As a reminder you do not have to answer any question you do not feel comfortable with and you may stop the interview at any time. You can ask me questions of your own at any time. The purpose of this interview is to help me understand how library study space is used by students and if this usage supports academic student engagement.

1. What does the library mean to you?

Probe: What role does the library play in your academic life here at Brock University?

Probe: How does the library help you with your course requirements and assignments?

2. Do you use library study areas?

Probe: Where do you study? How frequently (daily, weekly, length of time)?

3. Do you meet with other students in the library to study?

Probe: Where do you meet? How frequently (daily, weekly, length of time)?

Probe: Who do you meet with?

4. Where do you prefer to study in the library?

Probe: Does this depend on certain factors (nature of your assignments, time constraints, availability of other students, other factors)?

5. What do you do when you study in the library?

Probe: Reading, writing, working on your laptop, consulting with other students, using library computers to find books/journal articles, etc.

6. Assuming that some of your study time in the library includes activities (other than those we’ve just discussed above) what are some of these activities?

Probe: Leisure/recreational activities such as talking on your cell phone, having some food/drink refreshments, playing computer games, resting, etc.

7. Do you think the library is a “good” place to study?

Probe: Why and how?

Probe: Where else on campus or elsewhere do you study?

8. How do you think the library could help you more with your studying?

Probe: Are the study areas useful to you? How would you change these or improve them?

9. Do you ever ask for assistance from library staff?

Probe: Who do you ask, when, and where do they work?

Probe: How often do you ask for assistance?

Probe: What factors influence your decision to ask for assistance?

10. How do you think the library could make changes that would encourage you to use the library more?

Probe: Would more social spaces be better for you? What would these be? Where would these be?

Summary of what I heard:

What does the library mean to you?

To students who use the library, the library generally means a place to get resources, a place to study, and place to ask for assistance, and a place to meet fellow students. Students recognized the library as a resource centre and a place that supports their study efforts.

P – “My friends tell me that I eat, sleep and awake at the Library. I don’t work at home, too many distractions!”

M – “The library to me is a place to be around other students, to be with them in an atmosphere that seems to support learning. I want to fit in with my fellow students (I consider myself to be a mature student, I guess). I feel like one of the group when I’m in the library”.

A – “I think of the library as a resource centre and place to get assistance. What would we do without it? Even if there’s so much stuff now on the internet you still need to use library materials. The library doesn’t always have the journal articles I need online but they often have some of them in the stacks. Also I can use the interlibrary loan system, RACER, to have staff get stuff for me.”

Do you use the library study areas?

Students made extensive use of the library study areas, by and large. All expressed preferences for quiet areas and group study areas, depending on the nature of their work. If they needed to be more focused, or their working styles were more individual, students wanted and used individual study. If their work demanded group work with fellow students, then they made extensive use of whatever group areas they could find.

P – “I use the library every day, weekends and nights as well. Usually I work on floor 9 or 10 if I want to be by myself, or want to pay attention more. Floor 10, definitely during exam times if I can get a spot”.

M – “The first floor is where I always work. It has the most comfortable seating (both the soft seating in the lounge areas and the study carrels too) and the tables and desks can be moved around to some extent if you need to do that with group work”.

A – I don’t use the library that much to study since I like to use the graduate loan in my department whenever possible and also I like to work in quiet areas like my apartment. I don’t think noisy group study areas are for me. I’m mostly an introvert”.

Do you meet with other students in the library to study?

Students do meet fellow students in the library and this depends on the type of work they are doing. If they are attempting to be more focused and prefer to work alone then they do not meet up with other students during their study times. They may meet with other students for breaks or to take some time off from their studies in this case but generally if they are trying to concentrate they don’t make a habit of meeting with other students. If, on the other hand, they are pursuing group work then the very nature of that work demands that they work together. Apart from this, however, all students admitted that there are many instances during the day, week, month, where both types of study styles (individual or group) intersect and they go from one to the other almost seamlessly.

P – “We meet up with other students and friends sometimes. I don’t go there to socialize but the library is still the best place to meet your friends. It’s so central to everything for me”.

Where do you prefer to study in the library?

Students had definite preferences where they preferred to study. Individuals usually said that they preferred a certain floor for individual study (for example, floor seven) and tried to work at these preferred areas whenever possible. Group study preferences show a similar pattern. Students noted a severe shortage of these some of these areas at various times they wanted to use them.

P – “When we want to work on a project, the library is the best place to study, so we meet there, usually on the first floor but sometimes on floor 7, or even in a study room if we can get one. Other times we meet in library when we want to meet after class or to go somewhere else, say a class, or just to get together for a short time”.

M – “I like to chill out in the library, especially in the soft seating chairs. They are very comfortable and I do a lot of in-depth reading there on the first floor”.

What do you do when you study in the library?

Students noted reading, working on assignments, writing, reviewing or going over notes, literature searching, “thinking”, ……etc….

P – “Usually I work on my assignments. I read textbooks and journal articles, get reserve readings and make notes. I do literature searching for other articles.”

P – “I borrow laptops from the library and use the computers to do my assignments”.

M – “I prefer to work alone if possible. I do a lot of reading (humanities classes) and I need to concentrate on translations, etc. If I write an essay in the library I tend to only do drafts there. I prefer to work on polishing essays at home or the labs”.

Assuming that some of your study time in the library includes activities (other than those we’ve just discussed above) what are some of these activities?

Students mentioned eating and drinking or simply snacking or having lunch or dinner while studying. Everyone noted that they brought refreshments with them or went out of the library and purchased refreshments from time-to-time during their time spend in the library.

P – “Sometimes I might take a nap for a few minutes, or just relax by putting my head down and closing my eyes. I like to eat some food and drink some coffee or water. I do this so often I hardly even notice I’m doing it. I don’t use my cell phone that much but I have used it in the library once and a while. I don’t play computer games but I know some students do that sometimes”.

Do you think the library is a “good” place to study?

Everyone said the library was an excellent place to study, even if they added comments about the lack of enough study space or other grips about study spaces, student behaviors, or library service constraints.

K – “The library is a great place to study. I am very happy with the space that is provided for study”.

H – “The computer labs are not as good as the library for “studying” because there is more goofing off going on over there (computer commons, but in other labs too) I have noticed. More students use cell phones and chat it up with friends. Plus the desk space is really cramped”.

A – “I’ve used the sky bar lounge at Alphies for studying and it can be good, especially during exams because it isn’t used as much then and it’s quieter”.

A – “I think the library is the ideal spot to meet other students. It’s central and everyone knows where it is in the Schmon Tower, even if they only know the main entrance. I often meet people just inside the doors of the library and go other place with them or we get study carrels together”.

A – “It’s the best place to work in a quiet area with your laptop. There could be way more outlets but at least when you find one you can use it and it’s usually quiet on most floors. I can tolerate some low talking and that often happens on the floors but not enough to bother me”.

A – “I like to hang out in the library between classes or to spend lots of time studying or working on assignments. It’s a safe place to be. There is a good level of trust, I think, and students can leave there things at desks or carrels without that being a problem”.

H – “The library is the only place available on campus to do group work. I mean the cafeterias and maybe some class rooms could be used when they are not too busy or not in use but they are not set up for study in groups. The food court atmosphere in cafeterias is too noisy, messy, and the lighting is terrible”.

How do you think the library could help you more with your studying?

Students offered some advice about improving library services.

K – “I also use the Taro labs because I am a business student and we have access to these two labs. They are open 24 hours so sometimes students can even stay overnight and work. The labs are card-swipe access so they are secure. I feel safe working there with fellow students. Campus security comes by at night and checks on things so it’s no problem. How come the library doesn’t have labs like this”?

K – “I have noticed that photocopying is cheaper when you do it at the student centre. Why is this? How come the library can’t be as inexpensive and how come students can’t use a credit –debit system for photocopying like they do in the labs”?

A – “Definitely we need more quiet spaces. I like to work alone for the most part and don’t like too much socializing that I see going on in those group areas”.

Do you ever ask for assistance from library staff?

All students admitted to asking for help from various library staff.

P – “I ask for help all the time or I mean when I need to know something, how to find an article from a database I’m not familiar with or in case I’ve missed something. The staff at the reference desk is always very friendly and I’ve been lucky with my questions. The people there have usually been able to help me. Even the peer assistants have been good for me. They know the webct system and how to help you through registration problems, problems with printers and other technie stuff”.

M – “I like to ask for help a lot, but only do it sometimes. I’m lazy I guess! Or maybe I

know more than I know, or gradually get the information I need from friends or just trying my best, you know like trial and error method. Maybe I should ask more often”.

How do you think the library could make changes that would encourage you to use the library more?

Students mentioned the following suggestions that they felt would help them use the library more and/or make them feel more comfortable.

K – “I have noticed some things that need fixing. There are some window blinds on floor 7 that don’t work and when I study there I can’t get the sun shaded out. There are also lighting problems up on floor 7. Sometimes I have seen lights go off and on in the compact storage areas. Are there switches there? Why does staff shut off these lights? It is dark enough already up there”.

K – “I would really like to have a coffee shop or some sort of food service in the library. I don’t like to have to go out when I’m studying and if I haven’t got any food with me then this is a disruption for many students, I think. On weekends this would be really cool because nothing else is really open on campus”.

H – “There needs to be more study space, period! This campus is way too small for so many students. We need more individual and group spaces and even more library labs”.

H – “We need more outlets for our computers! There are too few plugs for laptops and we will need more of these all the time”.

H – “I like to work throughout the day and often there is a flow if you can get started on a project and work through it over a period of time. I bring my stuff in early in the day and get a study space somewhere, leave my stuff and come and go all day long. Being able to get food right in the library would be a real bonus so I wouldn’t have to waste time going out and coming back in. It would be more convenient and friendly I think”.

M – “How about getting more pictures on the walls, more outlets for computers, and better low-level lighting? I think that the library should design more of a “living room” atmosphere to the main floor study areas. How about even having some plants? How about a pet bird, like a parrot even, or a cat that would be resident in the library? I realize there may be lots of custodial issues with pets but wouldn’t it be cool, and wouldn’t that make an impact on your people-friendliness?’

M – “We need more copies of some papers like the Globe and Mail. I like to read it everyday but I’ve noticed we don’t get it right away that day. Why? More than one copy would be appreciated especially by international studies I think”.

M – “More online sources (databases and journals) are needed. I try and get all my articles online if I can”.

Bennett, S. (2005). Righting the balance. CLIR Reports (pub 129). Retrieved June 11, 2007, from http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub129/bennett.html

Charon, J. (2001). The nature of “perspective”. In J. O’Brien & P. Kollock (Eds.), The production of reality: Essays and readings in social interaction (pp. 19-24). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge.

Entwistle, N. J., & Peterson, E. R. (2004). Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: Relationships with study behaviour and influences of learning environments. International journal of educational research, 41, 407-428.

Gibson, C. (Ed.). (2006). Student engagement and information literacy. ACRL: Chicago.

Hu, S., & Kuh, G.D. (2002). Being (dis)engaged in educationally purposeful activities: the influences of student and institutional characteristics. Research in higher eduction, 43(5), 555-575.

Jacoby, J., & O’Brien, N.P. (2005). Assessing the impact of reference services provided to undergraduate students. College & research libraries, 66(4), 324-340.

Katzer, J., Cook, K. H., and Crouch, W.W. (1998). Evaluating information: A guide for users of social science research. Boston: McGraw.

Krause, K., Hartley, R., J.R., & McInnis, C. (2005). The First year experience in Australian Universities: Findings from a decade of national studies. Canberra: DEST. Retrieved June 15, 2007, from http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au

Milem, J. F., & Berger, J.B. (1997). A modified model of college student persistence: Exploring the relationship between Astin’s theory of involvement and Tinto’s theory of student departure. Journal of college student development, 38, 387-400.

Nardi, B. A., & O’Day, V. L. (1999). Information ecologies: Using technology with heart. Cambridge: MIT.

O’Connor, R. (2005). Studying a Sewanee education. Sewanee: The University of the South, Library Planning Task Force, Final Report for the Jesse Ball duPont Library.

O’ Connor, R., & Bennett, S. (2005). The power of place in learning. Planning for higher education, 31 (June-August), 28-30.

University of Massachusetts, Boston, W.E.B. DuBois Library. (2007). Learning commons assessment. Retrieved June 11, 2007, from http://www.library.umass.edu/assessment/learningcommons.html

Zeisel, J. (1975). Social science frontiers. New York: Russell Sage.